In a few weeks time the captain of the winning World Cup team will hold aloft the William Webb Ellis Cup. It was named as such in 1986 by John Kendall-Carpenter, the Chairman of the World Cup organizing committee for the first ever Rugby World Cup finals held in 1987.

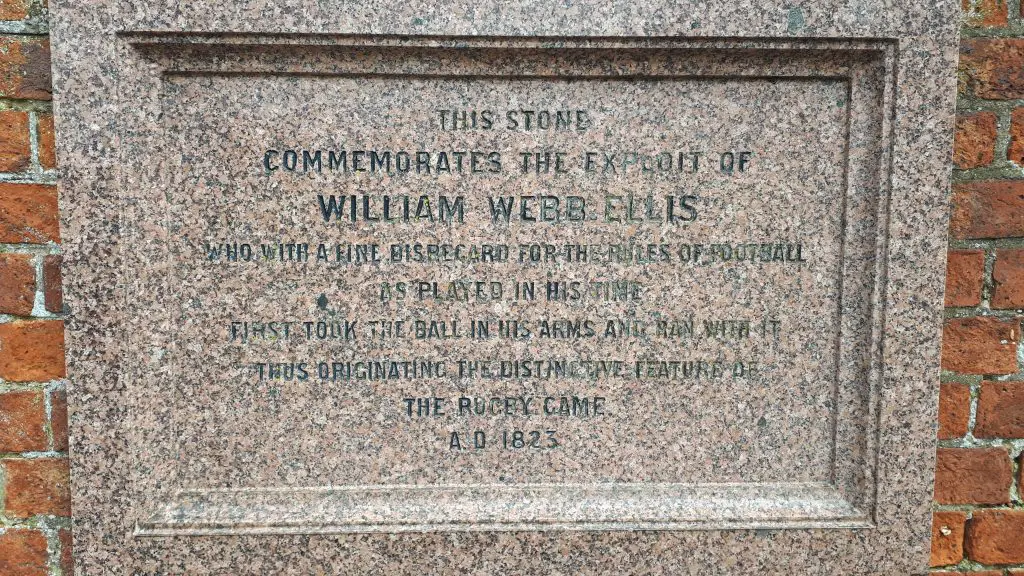

The simple origins of rugby story is that in 1823 William Webb Ellis picked up a ball at Rugby School and instead of kicking it, ran with it – and the game of rugby was born. A good story for sure. But the more complex, ‘real’ story is way more interesting.

About two hours drive north of London, England, lies the town of Rugby (population 70,000). It has the distinction of being known worldwide as the home of the game of Rugby. More specifically, it is Rugby School, in Rugby, where the game as we know it emanated.

Photo credit: Malcolm Anderson

William Webb Ellis and the birth of rugby

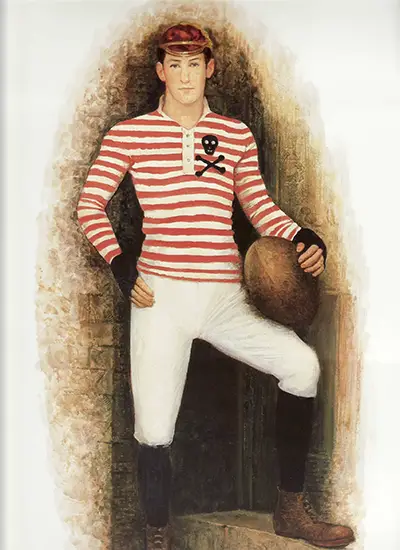

William Webb Ellis (WWE) entered Rugby School in 1816. After Rugby he went to Oxford University, about 45 miles away, where he completed his Bachelor of Arts and Masters degrees, then studied theology, and later became a clergyman in the Anglican Church. He played in the first ever cricket match between Oxford and Cambridge. He died in France in 1872 and is buried in Menton, which is about a 20-minute drive from Monaco in the south of the country, close to the Italian border. Rugby players and supporters frequently visit his grave.

There’s an inscription about WWE on a wall at Rugby School that reads: “who with a fine disregard for the rules of football first took the ball in his arms and ran with it …” He may well have done so, but the research scholars who dig deep on these things have not found any solid evidence that William Webb Ellis truly was the originator of the game. In fact, the primary source of the story only emerged 43 years later in 1876, four years after William had died. And that story was in a letter written to The Meteor, the Rugby School magazine, by a former Rugby school pupil. A more detailed description followed four years later from the same former pupil.

Photo credit: Rugby School

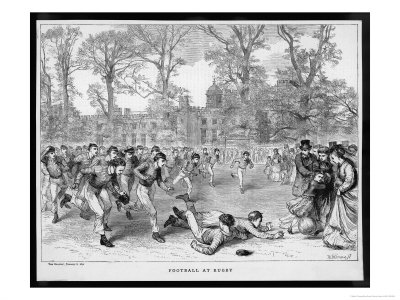

Evidence suggests that running with the ball became more common later in the 1830s, even though it was still forbidden, and one student in the late 1930s in particular – Jem Mackie – was well known as the great ‘runner-in’. A meeting at Rugby School formally legalized running with the ball in 1842.

The Old Rugbeian Society decided to investigate the WWE claim in 1895, and was “unable to procure any first hand evidence of the occurrence.” What was also clear is that whatever WWE did in 1823 did not result in a change of the rules. We’ll come back to the rules in a minute.

WWE or not, there were several things that did happen in the 1800s that led to the development and expansion of the game. We can owe this evolution to Rugby School in several more interesting and accurate ways than WWE’s running with the ball in 1823.

The playing field

Prior to the emergence of rugby football and football (soccer) ‘folk football’ that had emerged from medieval times was played over great distances by dozens of people (sometimes more than a hundred).

There is a town in England – Ashbourne (population est. 9,000) – that starts a 2-day match annually on Shrove Tuesdays (8 hours each day), and has been doing so every year since 1667, possibly earlier. It’s known as the Royal Shrovetide Football Match. The town is divided into two teams depending on birthplace. The teams play to get a leather ball to one of two goals north and south of the town centre (about 3 miles apart). The ball is seldom kicked, even though its legal to do so. Mostly it’s carried or thrown and moves through Ashbourne in hugs, which are like a giant scrum in rugby, and could be made up of dozens of people (and sometimes hundreds).

The public schools in England – in particular the ‘sacred seven’ ancient medieval schools, including Rugby School which had been established in 1567 – each developed their own set of rules depending on their own surroundings and often also in the relatively confined spaces of their schools. Rugby School had the advantage of a large piece of grass – The Close – and because of this was able to play a game that was much more physical and combative compared to the other schools, and more like the folk football of medieval times. In contrast, historians suggest that the narrower spaces and/or cobblestones of other schools meant the folk football was more likely to evolve into what we know today as soccer (hand-free football).

Read more about the rugby field…or is it a pitch?

Photo credit: Rugby School

Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold was the Headmaster at Rugby School between 1828 and 1842. He developed a ‘revolutionary’ model of education that focused on the growth of the boys beyond just learning subjects – their health, their moral compass, their character, the development of young men who were selfless and well-rounded. Healthy body – healthy mind.

Thomas Arnold never directly made a connection with the game of rugby but it was on the fields that the boys could test themselves – and the game was also a place where they could direct their built-up energy and any aggressive tendencies. His new model of education was replicated across the country (and overseas), especially in new schools, as was the game of rugby. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, was one of the biggest admirers of the model of teaching and physical activity at Rugby School, and a fan of rugby. “Organised sport can create moral and social strength”, wrote Coubertin.

Rules of Rugby

Whether it was rugby football or soccer, the schools would each have its own set or rules. Which was fine if the only games played were within each school. But as these schools began to play against one another (and later as town clubs emerged) there needed to be some agreement as to what the rules would be for all the schools, rather than teams showing up and having to discuss whose rules would be played by prior to each game (which is what would happen).

The first ever rules for football – rugby or soccer – were those developed in 1845 at Rugby School for its version of football. These original rules were for those who already understood the game played at Rugby School. The focus of these rules was on the parts of the game that were often disputed. This makes a lot of sense as the newer boys always coming into the school each year would need to know what the specific rules were at Rugby compared to what they knew from elsewhere.

In 1844 a committee of eight senior students at Rugby School was formed by the School’s Headmaster to write the rules. Several months later the work was passed on to three students, one of whom was William Arnold, the son of the former Headmaster. Within three days they created 37 rules. These rules were put before a student committee and approved. A rule book was printed. It was a small rule book – the idea being that it could be carried onto the field in the pockets of players’ trousers and used as required to settle any disputes.

The rule book provided consistency for how the game should be played. This not only helped the new students but also enabled the game at Rugby School to later be spread to other schools and to universities, or town clubs interested in rugby. The rules at Rugby School were updated annually as required. What we play today has evolved from those original rules. Later, in 1863, soccer developed its own set of codified rules after a series of meetings held in London by The Football Association (FA). Its initial set of rules still included running with the ball, but eventually this was dropped and soccer slowly evolved. In soccer’s early years, there were just as many rugby teams as soccer teams as members of the FA.

The Rugby Rules became increasingly known among schools and clubs in communities. But teams would still adjust the Rugby School rules depending on their own context. Recognizing the inconsistencies, in 1871 the newly created Rugby Football Union (RFU) set about standardizing the Rugby School rules. That task was given to three ex-Rugby School pupils – all lawyers – who instead of creating standardized rules, created the laws of rugby. Over the latter half of the century British settlers and the military took the game of rugby to other countries in the British Empire such as Australia, New Zealand [Internal link to NZ article] and Canada. The first match recorded in Canada, for example, was in 1865 in Montreal between military officers and a local team comprised mainly of McGill University students.

The Rugby Ball and the Gilbert Company

The official World Cup rugby ball can be traced back to Rugby School. William Gilbert made boots and shoes in a shop across the road from Rugby School on Lawrence Sheriff Street. He started making balls in the 1820s. His early rugby balls were much rounder than the current ball we boot around today. Some researchers would call it a plum shape. This is because it was a pig’s bladder that determined the exact shape of the ball. At that time, the bladder had to be blown up manually, and was then encased in leather.

Meantime, another, younger cobbler – Richard Lindon – opened a store a few doors away from William Gilbert, also directly opposite Rugby School. Although he made shoes it would be the manufacturing of balls that would become his big seller. Lindon’s wife would blow up the balls he made, but it was a risky undertaking if the deceased pig was diseased. Rebecca Linton, in fact, a mother of seventeen children, got a form of lung disease and died.

Photo credit: Rugby School

Richard Lindon designed a uniform ball that was the oval shape we have these days. He became the supplier of balls to Rugby School, and by 1861 he was supplying balls to Oxford, Cambridge and Dublin universities. In 1862 he invented a rugby ball made of the then new material, rubber. He also made an inflator that would pump air into these new rubber balls, which were, as before, encased in leather, with four panels.

Richard Lindon’s oval shaped rugby balls became the standard and he, then his son, made these rugby balls for fifty years. Richard Lindon is known as the inventor of the rugby ball, the rubber inflatable bladder and the brass hand pump. Unfortunately for he and his family he did not patent any of these innovations. One of his original rubber balls, estimated as being made in 1854, was discovered in an old chimney at Rugby School. He died in 1887.

William Gilbert died ten years earlier in 1877. His nephew James continued the business and was making about 2,800 balls a year. He started exporting balls overseas (e.g., Australia) and the business grew quickly. The Gilbert family decided to sell the business in 1978 but it wasn’t until 2002 that Grays of Cambridge International Limited bought the company. Grays itself has been operating since 1855.

Tom Brown’s School Days

Rugby School was immortalized in the book ‘Tom Brown’s School Days’, written by Thomas Hughes in 1857 (for his eight-year old son who he had intended to send to Rugby School but who unfortunately died before he got to the School). Thomas Hughes himself started at Rugby School in 1834.

Photo credit: Rugby School

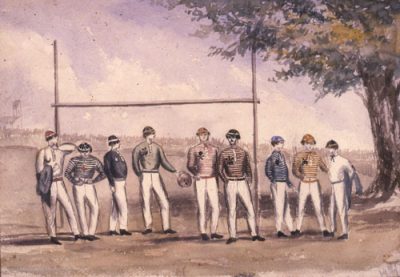

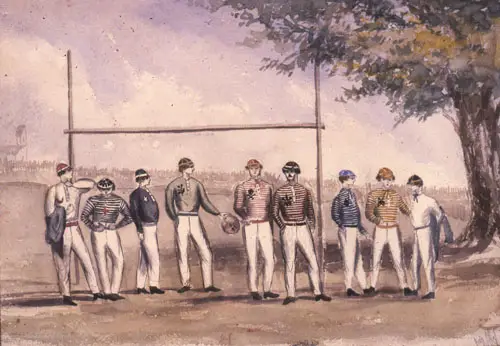

Tom Brown’s School Days is set in the 1830s. Tom is an injured hero who saves the rugby game in the last minute of play. Hughes describes the game, including the H-shaped posts. The book was a huge bestseller; 11,000 copies were sold in the first few months, and within forty years there had been 50 editions printed. It is a classic novel still printed today. Rugby football was becoming even more well known, and the description of the game of rugby that Tom played led to its uptake by the book’s readers; especially students of all ages. Meanwhile, the very first rugby clubs started forming in the 1850s. Some of the earlier rugby clubs apparently decided to use the Rugby School Rules after their reading of Tom Brown’s School Days.

“But now look! there is a slight move forward of the School-house wings, a shout of “Are you ready?” and loud affirmative reply. Old Brooke takes half a dozen quick steps, and away goes the ball spinning towards the School goal, seventy yards before it touches ground, and at no point above twelve or fifteen feet high, a model kick-off; and the School-house cheer and rush on. The ball is returned, and they meet it and drive it back amongst the masses of the School already in motion. Then the two sides close, and you can see nothing for minutes but a swaying crowd of boys, at one point violently agitated. That is where the ball is, and there are the keen players to be met, and the glory and the hard knocks to be got. You hear the dull thud, thud of the ball, and the shouts of “Off your side,” “Down with him,” “Put him over,” “Bravo.” This is what we call “a scrummage,” gentlemen, and the first scrummage in a School-house match was no joke in the consulship of Plancus.”

Photo credit: Rugby School

England Rugby

In the first ever international rugby match, played in Edinburgh in 1871 between Scotland and England, of the twenty English players (yes, 20!), ten were ex-Rugby school pupils (Old Rugbeians). The first five presidents of the Rugby Football Union were Old Rugbeians. The first England captain went to Rugby School. The tradition of international caps being awarded to players representing their country comes from the cap system that orginated at Rugby School (velvet caps were worn in the late 1830s by the senior boys). The white shirt and shorts and the black socks of the England team also come from Rugby School.

Rugby School Today

Rugby School became co-ed in 1975. Nowadays 10% of its student body are from overseas. The School’s mantra these days is ‘The Whole Person is the Whole Point’. Headmaster Thomas Arnold would be proud. Rugby School is the home of rugby, and the fields – The Close – and the school itself, look much the same way as they did when the game of rugby that we play today, began.

Photo credit: Rugby School

You can visit the school and take guided tours that reveal its history, and also visit its museum. And if you want to get a good idea of what the game of rugby was like in the 1830s, get inspired by reading Tom Brown’s School Days.

About the author: Malcolm Anderson is a sports writer based in Ontario, Canada. Originally from New Zealand, his primary focus is rugby and distance running. malandersonwrites@gmail.com